A Fresh Take on the Pomodoro Technique

Monique Dufour

Faculty Fellow, Faculty Affairs

Associate Collegiate Professor, History

Have you heard of the Pomodoro Technique? When I began working with faculty writers over ten years ago, few people knew about this time management method. Now, when I ask writers at workshops if they are familiar with it or use it regularly, hands shoot up.

It works like this: choose a task, set a timer for 25 minutes, and focus on that task without interruption. When the timer goes off, take a five minute break. Each 25-minute work session is called a pomodoro. After completing four “pomodoros” in succession, take a 30-minute break. (It’s named “pomodoro” because the person who popularized it was Italian, and he used a little analog timer that looked like a tomato.)

Some writers swear by it.

But, many writers have also confessed to me that the pomodoro technique just doesn’t seem to work for them. They tell me that they have followed it to the letter, working for one 25-minute period after another. They put in the time and effort, yet they end up feeling frustrated and ashamed that they aren’t making progress. It’s disappointing and draining., Worse, it feels like their fault. Surely, if this foolproof method does not work for them, then they must be the problem.

I worry when I see yet another writing panacea make the rounds. “Just write for 30 minutes a day.” “Just set a timer for 25 minutes and work without interruption.” “Just put in on your calendar.” “Just lower your standards.” “Just do what I do.”

The Pomodoro Technique can work well for many people, if we understand where the magic and power resides, and if we adapt it for our own needs and circumstances.

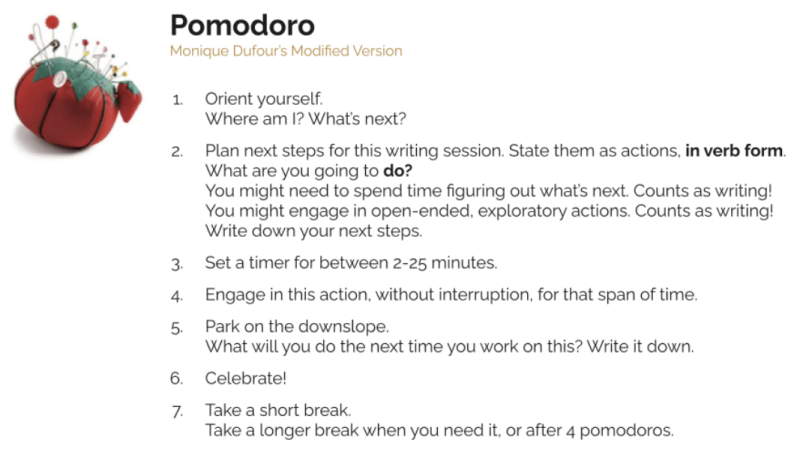

I’ve created my own modified pomodoro technique, one that helps us to acknowledge and capitalize on its powers.

1. Orient yourself.

I once heard Kel Weinhold, a great writing coach, explain why writing can be so painful. When we sit down and begin to write, they explained, we often read down to a part that we feel bad about, and then try to fix it. No wonder writing becomes a grind, and that even beginning can fill us with dread. We literally skim to a pain point and linger there. We are discouraged and drained before we have even begun.

When you begin your first pomodoro, don’t just open the document and start doing whatever comes to mind, likely “finding and fixing the bad parts.” (Unless you have a great deal of momentum on the project and absolute clarity about what to do next—more on that below at step 5.)

Instead, take a moment to orient yourself to the project. Treat these opening moments as a kind of arrival in your work. You’re touching down and looking around. Take out your compass. Do you have a sense of where you are? Is this familiar territory or a deep wood without a path? Is there far to go? Where might I head next?

2. Plan your next actions for this writing session. Write them down in verb form: as something you can do.

“Writing” is a global verb. This one capacious word refers to a wide array of possible actions. When we set out to “write,” it sounds like we are doing just one thing. But, when we are writing, we are always doing something more specific, and then something else, and then something else. When the writing is flowing, we are often unconsciously doing one thing after another in a way that feels natural, even effortless. We think of an idea, then type some words, then read over those words and revise them, then chase the train of thought by typing more sentences, then remembering a book that raised a related idea, then getting up and scanning the bookshelf, finding the book, and paging through it. You get the idea.

So, even when we are in a flow state, we are in fact doing a lot of different things. We may not feel that we are explicitly deliberating about what to do next. But we are often task switching.

This is important to understand because, when I suggest that people establish specific actions in their pomodoros, they often resist on the grounds that they just want to write naturally. They prefer the flow state, and they want a process in which it just happens without deliberate effort. However, when we avoid intentional action in pursuit of “natural” flow, we misunderstand what a flow state even is—relegating decision making about what to do next to a less conscious (and often habitual) state.

We are more likely to ease into a flow state through the rather counterintuitive practice of beginning in a deliberate, intentional way: by articulating our next actions in verb form. That way, we can initiate a string of actions by taking the first one.

So, what is the first thing you are going to do as you begin writing during this pomodoro? Write it down as a specific, actionable verb. This can break the trance of staring at the screen or ruminating about the project as a whole, because you have made writing actionable.

Keep in mind that there are all kinds of actions that you might choose. It might be a good time to engage in concrete, well-bounded tasks, which are easier to name and knock out: format the footnotes or obtain PDFs of texts on your source list. Or, you might decide to explain a concept or describe a step in your experiment. Other times, you may choose more open-ended verbs: brainstorm possible ways you could organize a section, free write about an important but as-yet-unformulated idea.

Interested in learning how to plan next actions? Attend a writing retreat, where I offer workshops on the topic.

3. Set a timer.

The official pomodoro technique specifies that you work in 25-minute increments. However, you are free to set any amount of time. Many writing groups such as London Writers Hour and Danna Agmon’s Wednesday Writers Group work for 50-minute blocks.

If you have been struggling to engage with a project, or if you are feeling apprehensive, I recommend that you set a timer for two minutes. Establish a tiny step that you can take, and do that for just two minutes. Most people find that a few very short writing sessions help them to do the hardest thing: to begin again. Then, try five minutes for a while. Maybe 10. Friend, you can go the whole way that way.

Working with a timer also helps you to constitute your writing process as an object of study. Notice how it goes as you work for different amounts of time on a range of projects and under a range of conditions. When you become curious about your writing process, you will learn how long things take you--a rare insight!--and how your experiences and outcomes are shaped by the work and by the conditions of your own mind, body, and life.

4. Focus on your project, without interruption, for your set period of time.

At each London Writer’s Hour, the host reminds writers of Neil Gaiman’s rule for writing sessions: “write, or do nothing.”

You may often feel an urge to step away—even to flee—from your writing. Maybe you think, “If I just knock out this one thing”—send an email, respond to one student’s work, empty the dishwasher—then I can work. By committing to working during the timed period, you have a way of working with resistance and distraction (which often accompany your writing together).

When you work in timed sessions, you reap the added benefit of discovering how long things take. We often underestimate how long projects take. And we often put off tasks that turn out to be easily and swiftly done.

5. Park on the downslope.

At the end of each pomodoro, take a moment to ask, “What is the first thing I will do the next time I work on this?” Write it down.

I use the analogy of a bicycle to explain. Imagine you have a magic bicycle. You can leave it outside, and no one can take it. It’s there, ready for you to ride at any time. You love this bike. The only catch: you must park it in the middle of a hill, and you must ride it in the direction that you parked it.

If you park the bike facing uphill, you will need to pedal very hard right away to get the bike moving. Given how hard it will be to start riding, you may rarely even try. In fact, you may feel apprehensive and defeated at the very thought of that bike.

But if you park on the downslope, all you need to do to get moving is to throw your leg over it and take a seat. Ahhh, then you roll. Yes, you will need to pedal eventually. But you will already be in motion, and you will have momentum. The prospect of riding that bike becomes appealing.

When you park on the downslope in your writing, you end one pomodoro with the start of the next one in mind. You build momentum in your work when you make connections across writing sessions. This happens on the level of the pomodoro: ending each pomodoro by saying what you will do the next time you write will reduce the friction of starting again. You have the psychological and practical advantages of knowing that the bike is in position to roll.

6. Celebrate.

At my retreats, when I ask writers what they accomplished during a writing session, they often land on what they failed to do. “I wrote part of the methods section, but I didn’t do nearly as much as I needed to.” “I drafted the intro, but it’s terrible.”

Most academics have high hopes and higher standards, not to mention long to-do lists and looming deadlines. All the more reason that we need to build up good feelings around our writing practice. Celebration is the way, and it’s non-negotiable.

As Rick Hansen explains, our brains have a strong negativity bias. As a result, “negative experiences get captured in emotional memory instead of positive ones, gradually darkening your outlook, mood, and sense of self.” To prevail over this bias, he recommends the practice of taking in the good:

- Let positive facts become positive experiences.

- Savor the positive experience for 10-20-30 seconds. Try to let it fill your body, and be as intense as possible.

- Intend and sense that the positive experience is soaking into you, like water into a sponge, becoming a part of you.

At the end of each pomodoro, take in the good. Say what you accomplished, and spend a minute savoring it. Get that feeling in your body. Play a celebration song and dance. Fist pump. Jump up and down. You don’t need to believe it in your brain. Let your body do the work.

7. Take a break.

You are not a floating thought cloud. Get up and move your body. Rest or exercise your eyes. Do some stretches for writers.

And remember: email is not a break. Nor is swapping one kind of work for another. It just creates attentional fatigue. Instead, step away, knowing that you’ve developed a writing practice that will help you begin again when it’s time.